Introduction: Context and Importance

When Lyman C. Draper published King’s Mountain and Its Heroes in 1881, his goal was clear: to preserve, in permanent form, the memory of the frontier militias whose victory at the Battle of Kings Mountain changed the course of the American Revolution. Draper understood that the men who had fought in that struggle were long gone, but their descendants still carried scraps of oral history, letters, and relics. By capturing those accounts, he ensured that future generations would know that this was not merely a clash of armies but a people’s battle — fought by farmers, hunters, and settlers who took up their own rifles to defend liberty.

The Southern theater of the war in 1780 seemed bleak for the Patriot cause. Charleston had fallen, General Gates had been routed at Camden, and British forces pushed deep into the Carolina backcountry. Cornwallis moved northward with confidence, his army sweeping into Charlotte, which he derisively called a “Hornet’s Nest of Rebellion.” To him, Mecklenburg’s defiance was a nuisance; to the Patriots, it was a badge of honor.

Against this backdrop of apparent British dominance, the seeds of resistance began to take root. What Draper sets out to demonstrate — and what the story of Kings Mountain makes undeniable — is that ordinary frontier communities, when stirred to action, could achieve extraordinary results.

Frontier Background and Early Settlers

The story of King’s Mountain cannot be separated from the rugged world of the frontier. In the eighteenth century, waves of Scotch-Irish and German settlers pushed into the Carolina backcountry, carving homesteads along the Catawba Valley and across the ridges of the Blue Ridge Mountains. These settlers brought with them traditions of independence, hard work, and faith, which hardened into necessity on a landscape that demanded resilience.

Life on the frontier bred men who were self-reliant, skilled with the rifle and the ax, and accustomed to danger. Long before they faced Ferguson’s Loyalists, these same settlers had defended their families against Native raids, cleared dense forests, and survived harsh winters with little more than their own determination. When called upon to fight, they relied not on parade-ground drill but on instincts shaped by hunting and survival.

In Mecklenburg County, early roads and trading paths converged near what is now Huntersville, linking small farms to larger markets and to the political hub of Charlotte. These routes that once carried livestock and wagonloads of grain would, in 1780, carry armed militiamen as they answered the alarm and marched toward destiny. Draper emphasizes that the roots of the victory at Kings Mountain grew out of this frontier experience — a society that prized liberty because it had been earned through hardship.

The Spark: Ferguson’s Threat

The immediate spark that set the backcountry aflame came from Major Patrick Ferguson, a skilled British officer sent to organize Loyalist resistance in the Carolinas. Confident in his command and eager to intimidate, Ferguson issued a blunt warning to the mountain settlers: lay down your arms and submit to the Crown, or he would march his forces across the Blue Ridge and “lay waste to their country with fire and sword.”

Rather than cow the settlers, this threat galvanized them. At Sycamore Shoals on the Watauga River, hundreds gathered in defiance. They prayed, organized, and pledged to carry the fight eastward before Ferguson could descend upon their homes. Draper highlights this moment as one of frontier determination, when ordinary men decided to become extraordinary soldiers.

The spirit of resistance had roots in earlier generations of pioneers. The memory of Boone — Daniel Boone, whose hunting trails and courage had already become the stuff of legend — loomed large over the Overmountain country. Boone’s example of crossing ridges, defying threats, and carving out settlements in hostile territory inspired the militias of Wilkes, Washington, and Sullivan counties to take the offensive. In their minds, the fight at King’s Mountain was simply an extension of that same frontier struggle for survival and liberty.

The Overmountain Men Gather

Once Ferguson’s threat spread, the frontier rallied with remarkable speed. Leaders emerged from every valley: Colonel William Campbell of Virginia, Isaac Shelby and John Sevier from the Watauga and Nolichucky settlements, and Benjamin Cleveland from the upper Yadkin and Wilkes region. Each was a figure of local respect, hardened by frontier fighting and bound by loyalty to his men.

At Sycamore Shoals, they joined forces and organized their march. Hundreds of settlers arrived on horseback, rifles in hand, carrying little more than powder, shot, and determination. They were farmers and hunters, not professional soldiers, but their unity made them formidable. Draper describes their mustering as a moment of raw resolve — a people deciding to take history into their own hands.

Modern landmarks help us trace their path. In Ashe County, near what is now West Jefferson, men from scattered homesteads made the difficult trek to join the larger force. Together, the combined militias represented the strength of the Appalachian backcountry, each company bringing its own style of leadership but united in purpose. What began as scattered resistance quickly took shape as an organized march that would culminate at King’s Mountain.

The March Across the Mountains

The decision to confront Ferguson required more than courage — it demanded endurance. The march of the Overmountain Men across the Blue Ridge was one of the most grueling feats of the Revolution. For days they rode and walked through relentless rain, often shrouded in fog so thick that visibility shrank to yards. Trails were little more than muddy tracks; streams ran high, and every crossing soaked men and horses alike.

Despite these hardships, the Patriots pressed forward. They knew that delay could mean disaster, as Ferguson’s column was moving as well. The Overmountain force pushed eastward to unite with additional militia under Benjamin Cleveland and Charles McDowell. Cleveland’s men came from farms and hollows scattered throughout Wilkes County, a region that had already proven itself a wellspring of Revolutionary fervor. Draper records how the Wilkes militia added both numbers and spirit, ensuring that the expedition had the strength to continue.

By the time the combined forces descended into the Piedmont, they were cold, wet, and exhausted — yet undaunted. Their march over mountains and through storms symbolized the determination of frontier communities to risk everything rather than submit. What united them was not uniform or pay but the shared belief that their homes, families, and freedom were worth the struggle.

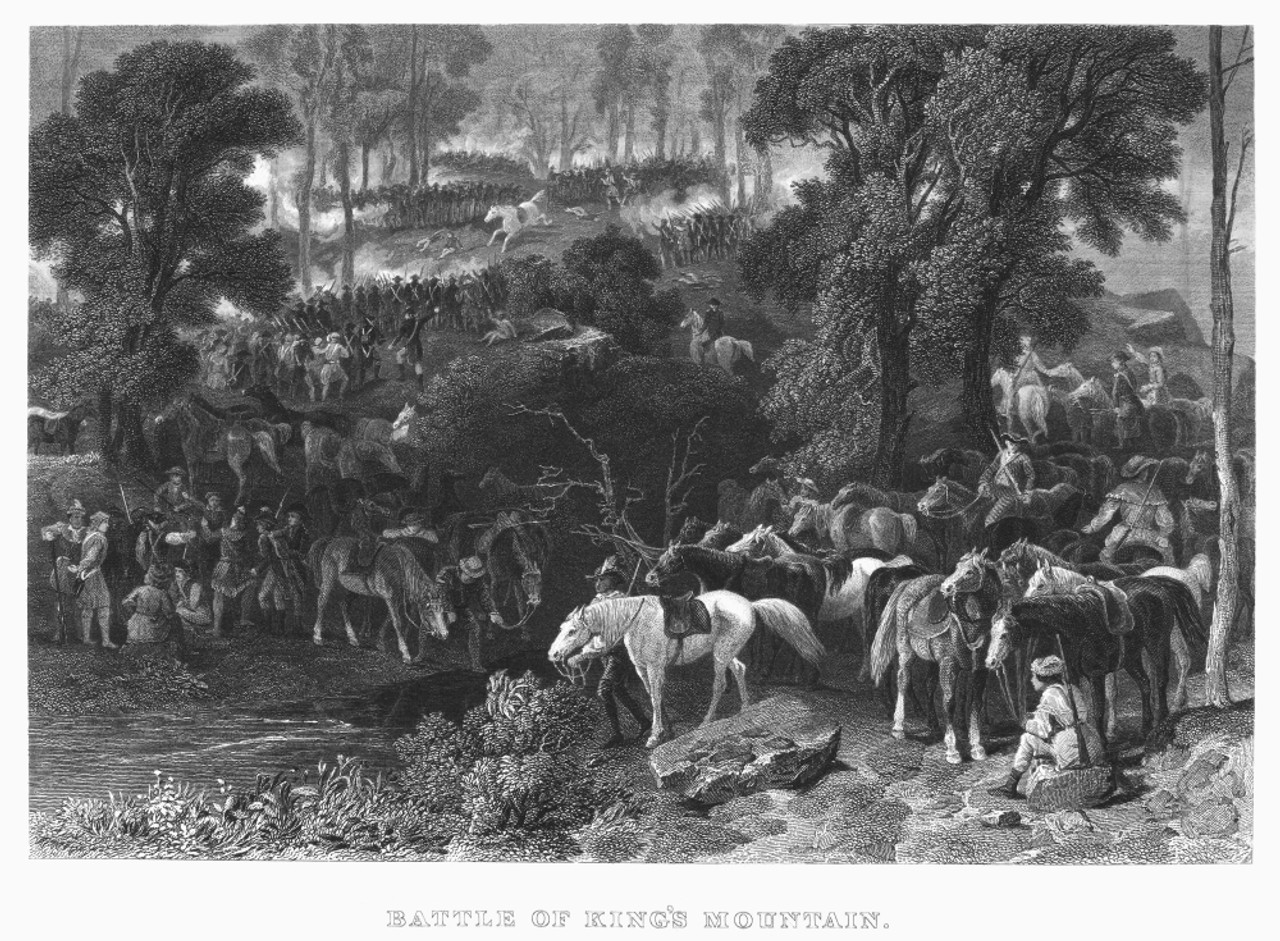

The Battle of King’s Mountain (October 7, 1780)

When the Patriot force finally caught up with Ferguson, they found his Loyalist army entrenched on the ridge of King’s Mountain, a rocky rise straddling the border between the Carolinas. Ferguson believed the high ground gave him an unassailable position, but the Patriot leaders saw an opportunity. They resolved to encircle the ridge on all sides, advancing uphill in waves of riflemen.

The fighting was fierce. Time and again, the Loyalists launched bayonet charges that drove the frontiersmen back. Yet each time, the militiamen retreated only far enough to reload before surging forward again. Their hunting rifles proved deadly in the wooded slopes, while the Loyalists’ bayonets lost their edge against such a fluid enemy. Gradually, the noose tightened.

Ferguson, rallying his men on horseback, became a conspicuous target. When he was finally struck down — shot multiple times and dragged from his saddle — the Loyalist defense collapsed. With their commander dead and casualties mounting, the Loyalists surrendered.

The victory at King’s Mountain was remarkable not only for its decisiveness but also for its character. This was a battle fought and won entirely by militia; not a single Continental officer or regular regiment was present. Men from Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and what would become Tennessee proved that citizen-soldiers could humble one of Britain’s finest officers. Among the ranks were volunteers from the Iredell and Rowan frontier, areas near present-day Statesville, whose contributions underscored the truly regional nature of the fight.

Draper calls King’s Mountain the turning point of the Revolution in the South, a moment when the tide of British momentum was decisively checked by the sheer determination of the backcountry.

Aftermath and Consequences

The scale of the victory at King’s Mountain stunned both sides. In barely an hour of fighting, the Loyalists suffered devastating losses: 225 killed, 163 wounded, and 716 taken prisoner. Major Patrick Ferguson, the architect of the campaign, was buried on the field where he fell, his body covered with stones by the men who had defeated him. The Patriots, though weary and bloodied, had accomplished what many had thought impossible — destroying a major British force with militia alone.

For the Patriot cause, the impact was electric. News of the triumph spread rapidly through the Carolinas and Virginia, restoring confidence after months of defeats at Charleston and Camden. Cornwallis, shaken by the loss, abandoned his advance into North Carolina and withdrew from Charlotte, conceding that the backcountry was far from pacified.

The ripple effect of King’s Mountain reshaped the Southern campaign. It opened the door to subsequent victories at Cowpens in January 1781 and Guilford Courthouse in March. Local memory also drew a straight line between the mountain triumph and sacrifices at other regional battlefields. At the Battle of Cowan’s Ford on the Catawba River in 1781, Patriot militia resisted Cornwallis’s crossing in a desperate stand, echoing the same spirit of defiance that had carried the day at King’s Mountain.

Draper emphasizes that this was the true turning point in the South. By breaking the momentum of British power and inspiring renewed resistance, the frontier victory at King’s Mountain helped set the stage for Yorktown and ultimate independence.

Biographies of the Leaders

The story of King’s Mountain is inseparable from the men who led the frontier militias. Each commander brought his own strengths, and together they formed the unlikely coalition that defeated Ferguson.

John Sevier was perhaps the most fiery of them all. A Tennessean by heart and temperament, Sevier’s charisma drew men to him, and his daring inspired them in battle. After the Revolution, his ambitions carried him into politics and eventually into the controversy of the Lost State of Franklin, an early attempt by western settlers to form their own government apart from North Carolina. Sevier’s role there reflected the same independence of spirit that had driven him to King’s Mountain.

Isaac Shelby was the organizer, a practical man of action who rallied support and kept his militia cohesive. His skill at planning and his coolness in command later propelled him to become the first governor of Kentucky, where he was remembered as a steady statesman who never forgot his frontier roots.

Benjamin Cleveland of Wilkes County was a larger-than-life figure whose reputation on the frontier was legendary. Known for his boldness and colorful personality, Cleveland embodied the rugged, self-made spirit of the backcountry. His leadership at King’s Mountain was both tactical and symbolic, representing the resolve of North Carolina’s mountain settlers.

William Campbell, the Virginian leader, brought discipline and courage to the field. Though he died young, his role at King’s Mountain left a lasting legacy, remembered as a commander who stood firm when the stakes were highest.

Together, these leaders demonstrated that diverse backgrounds could be united by a single cause. Their actions showed how character, determination, and vision could turn a gathering of militia into a force capable of changing the course of a war.

The Frontier as Identity

The victory at King’s Mountain was not just the product of numbers or strategy — it was the expression of a culture. The men who fought there were children of the mountains, raised in a world where survival demanded toughness, resourcefulness, and independence. Their upbringing on the frontier gave them the skills that proved decisive: marksmanship honed in hunting, resilience shaped by isolation, and a deep sense of responsibility to defend their homes and families.

This mountain culture also fostered an independence of spirit that carried into politics and identity. The backcountry people often felt disconnected from coastal elites, with different priorities and values. That sense of separateness lingered long after the Revolution. In later years, the mountain counties of North Carolina were sometimes referred to as the Lost Provinces of Western North Carolina — regions tied more closely to the rhythms of the frontier than to the centers of power in the east. The phrase captured both the geographic isolation and the fierce self-reliance of the people who lived there.

At King’s Mountain, that identity came into sharp focus. The men were not professional soldiers in uniform, drilled and disciplined by a central command. They were farmers, hunters, and settlers who drew strength from their land and their communities. Their victory proved that a uniquely frontier way of life could produce fighters capable of toppling one of Britain’s most skilled commanders.

Legacy and Memory

King’s Mountain has often been remembered as “the people’s battle.” Unlike the larger set-piece clashes of the Revolution, it was not won by regular regiments or directed by Continental generals. It was carried instead by volunteers — ordinary men who left their farms, gathered their rifles, and decided that liberty was worth the risk. This character has made the battle a touchstone in both North Carolina and Tennessee, a heritage shared across state lines and generations.

Today, the field at King’s Mountain is preserved as a national historic site, its trails and monuments reminding visitors of the sacrifices made in 1780. But the legacy lives on beyond the battlefield itself. Educational institutions across the region help carry forward the cultural memory of that fight for independence. In Boone, App State continues the mission of serving mountain communities, a modern echo of the same resilience that defined the Overmountain Men. In Charlotte, Queens University reflects the city’s deep historical roots and commitment to civic identity, while nearby Davidson College preserves traditions of leadership and scholarship tied to the history of the Carolina backcountry.

Together, these institutions show how the story of King’s Mountain endures — not only as a military triumph but as a symbol of what frontier determination and community spirit can achieve. The memory of the battle still shapes how the region sees itself: independent, resilient, and proud of a legacy where ordinary citizens once changed the course of history.

Regional Ties and Broader Influence

The courage displayed at King’s Mountain did not fade with the war’s end. Its influence spread across the Piedmont and the Catawba Valley, shaping how later generations understood resilience and community. The backcountry victory became a touchstone of identity, reminding people that even in the most difficult circumstances, ordinary citizens could rise together and achieve extraordinary things.

That spirit is still reflected in the towns and communities that grew from the same soil. Places like Cornelius, Davidson, Denver, Sherrills Ford, Terrell, Troutman, and Mooresville all carry forward the heritage of the Carolina backcountry. Though many of these towns developed much later, their roots stretch into the same land that nurtured the Overmountain spirit. Their schools, churches, and neighborhoods exist on ground once crossed by militias, and their sense of community echoes the determination of those who marched and fought at King’s Mountain.

By anchoring the memory of the battle to the growth of these towns, the story becomes more than distant history. It becomes part of a living landscape, where modern families inherit the legacy of frontier valor. The values of perseverance, independence, and unity that defined 1780 remain woven into the fabric of today’s Lake Norman and Piedmont communities.

Conclusion: The Mountain Stands

The Battle of King’s Mountain marked a decisive shift in the American Revolution. What had seemed like a march of British dominance after Charleston and Camden was broken in a single afternoon by a force of militia. Cornwallis was forced to retreat, his southern strategy disrupted, and Patriot morale restored at a moment when hope hung by a thread.

The battle remains more than a military event; it stands as a lasting symbol of independence, resilience, and the power of ordinary citizens to change the course of history. The men who fought at King’s Mountain were not regular soldiers — they were neighbors, farmers, and hunters who understood that freedom required sacrifice. Their example continues to inspire, reminding us that unity and determination can overcome even the most daunting challenges.

In modern scholarship, historians at UNCC and other institutions have pointed to King’s Mountain as the true turning point of the Southern campaign. Its lessons still resonate in the Carolinas and beyond: that communities bound together by shared values and resolve can accomplish what larger, better-equipped forces cannot.

King’s Mountain stands as more than a ridge of stone; it is a monument to the will of a people and the enduring truth that liberty is worth defending.

Adkins Law, PLLC: A Law Firm Located in Huntersville NC

At Adkins Law, PLLC, we are proud to serve families in Huntersville, Mountain Island Lake area, and the greater Lake Norman region. Just as the men at King’s Mountain stood for resilience and community, our practice is dedicated to guiding clients through life’s challenges with strength and clarity. Whether you need help with family law, custody, estate planning, or mediation, our team is here to stand by your side and protect what matters most.

Click here to contact Adkins Law, PLLC to arrange a consultation with an experienced family law attorney.

Leave a Reply