I. Introduction

When people think of the American Revolutionary War, they often picture Lexington and Concord in Massachusetts, or Yorktown in Virginia. But the Southern Campaign, fought between 1780 and 1781, was every bit as decisive. In fact, North Carolina’s backcountry became the battleground where the Revolution’s fate was sealed.

At the center of this struggle stood Charlotte — then a modest crossroads town at Trade and Tryon Streets — where British General Charles Cornwallis marched in after his stunning victory at Camden. Cornwallis expected little resistance as he moved north from South Carolina. Instead, he encountered a fierce and relentless population that stung his army at every turn. Frustrated, he compared Mecklenburg County to a “Hornet’s Nest of Rebellion,” a name that has defined Charlotte ever since.

The Revolutionary battles in and around Charlotte were not grand clashes of thousands like at Saratoga or Yorktown. Instead, they were smaller but no less significant fights: militia ambushes at crossroads, fords, and taverns that delayed Cornwallis’s advance, drained his supplies, and proved that the backcountry would never bend quietly.

These skirmishes connect directly to the broader Lake Norman region we know today. The Battle of Cowan’s Ford unfolded where Huntersville, Cornelius, Davidson, Sherrills Ford, and Denver now meet the waters of Lake Norman. The militia at McIntyre’s Farm fought just outside present-day Huntersville. Torrence’s Tavern stood near today’s Mooresville, not far from Davidson College. And to the west, communities in Wilkesboro, Boone, and West Jefferson carried the fight deeper into the NC High Country, forming a chain of resistance that tied the Catawba backcountry to the Blue Ridge. Even Newton, NC, played a role in preserving and honoring these Revolutionary legacies.

Charlotte’s Revolutionary story is therefore much bigger than the city itself. It’s a story of the Lake Norman towns and the North Carolina backcountry, of stubborn defiance in Huntersville and Cornelius, of sacrifice at Cowan’s Ford, of tavern brawls in Mooresville, and of mountain men streaming down from Boone and West Jefferson to join the fight. Together, these places earned the name Cornwallis never meant as a compliment: the Hornet’s Nest of Rebellion.

II. Prelude to Charlotte’s Battles

By 1780, the Revolutionary War had dragged on for five grueling years. In the North, George Washington’s Continental Army held on after hard campaigns around Philadelphia and New York. But in the South, the British saw an opportunity. They believed the Carolinas and Georgia were rich with Loyalists who would rally to the Crown if given the chance. If Britain could secure the South, they could then push north, cut off Virginia, and strangle the rebellion.

Siege of Charleston (May 1780) – Britain’s Big Win

The campaign began with a crushing blow to the Patriot cause. On May 12, 1780, after weeks of bombardment, Charleston — the most important port city in the South — surrendered. More than 5,000 Patriot troops were captured, the single largest American loss of the entire war. The fall of Charleston gave the British control of South Carolina’s coast and opened the backcountry to invasion.

Battle of Camden (August 1780) – A Patriot Disaster

The next test came at Camden, South Carolina, on August 16, 1780. General Horatio Gates, celebrated as the “Hero of Saratoga,” led about 4,000 Americans against Cornwallis’s 2,200 British regulars. The result was catastrophic. North Carolina militia broke almost immediately, and Gates himself fled more than 60 miles on horseback. Nearly 2,000 Patriots were killed, wounded, or captured. Camden left the southern backcountry wide open, and British confidence soared.

Cornwallis Marches North

With Charleston secure and Camden won, Lord Charles Cornwallis turned his attention to North Carolina. He envisioned an easy march north, gathering Loyalist recruits along the way. By early fall, his army — battle-hardened, confident, and numbering over 2,000 — crossed into Mecklenburg County. His next stop: the small crossroads village of Charlotte.

Mecklenburg’s Rebel Spirit

But Cornwallis underestimated the land and its people. Mecklenburg County was no ordinary backcountry. As early as May 1775, local leaders had adopted the Mecklenburg Resolves, declaring that British laws were null and void in their county. Some even claimed a full Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence had been signed — a year before Jefferson’s national Declaration. Whether or not the “Meck Dec” existed in written form, the sentiment was clear: Mecklenburg was already living as if it were free.

By the time Cornwallis reached the crossroads of Trade and Tryon Streets, he was not entering a Loyalist stronghold but a community that had practiced independence for five years. What followed — the Battle of Charlotte, McIntyre’s Farm, Cowan’s Ford, and Torrence’s Tavern — would prove that Mecklenburg’s rebellious spirit was more than just words on paper.

III. The Battle of Charlotte (September 26, 1780)

In the fall of 1780, Charlotte was hardly the bustling financial hub it is today. At the time, it was little more than a backcountry crossroads — two dusty paths intersecting at what we now know as Trade and Tryon Streets in Uptown. But on September 26, that quiet square erupted into one of the most dramatic small battles of the Southern Campaign.

Davie’s Stand at the Crossroads

Colonel William Richardson Davie, a young but fiery militia leader, had only about 150 cavalry and riflemen under his command. Knowing Cornwallis was advancing with over 2,000 British regulars, Davie had no illusions of winning a decisive victory. Instead, he set an ambush designed to sting, delay, and humiliate the British.

Davie positioned his men around the courthouse that stood at the center of Charlotte. They lined fences, hid behind buildings, and used the very streets of the town as their battlefield. This was unusual in the 18th century, when armies typically fought in open fields, not through alleys and yards.

Street Fighting in the Queen City

As Cornwallis’s vanguard advanced into the town, Davie’s men unleashed musket fire at close range. British troops fell in the streets. Confusion rippled through the column as redcoats realized they were being ambushed in a place they expected little resistance. Though outnumbered ten to one, the militia fought fiercely, retreating only when their flanks were overwhelmed.

Davie’s stand inflicted disproportionate casualties, a moral victory that showed Cornwallis the Carolina backcountry would not be easily pacified.

The Hornet’s Nest of Rebellion

Frustrated and embarrassed, Cornwallis later described Charlotte and Mecklenburg County as a “hornet’s nest of rebellion.” The phrase, meant as a complaint, became a badge of honor. Generations later, it would live on in civic symbols:

- The Charlotte Hornets NBA team, whose name directly traces back to Cornwallis’s remark.

- The Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police Department seal, featuring a hornet’s nest.

- Parks, schools, and neighborhoods across Mecklenburg that proudly carry the name “Hornets Nest.”

Legacy Beyond the Battle

Though the British technically captured Charlotte, their stay was short and miserable. Constant harassment by Patriot militia made it impossible to maintain control. Cornwallis would abandon Charlotte within two weeks, retreating southward before resuming his northward push.

The Battle of Charlotte may not have been large in numbers, but it was outsized in impact. It turned a quiet backcountry town into a symbol of Revolutionary defiance — the sting Cornwallis never forgot.

IV. McIntyre’s Farm (October 3, 1780)

Just one week after the skirmish at Trade and Tryon, the British learned again that Mecklenburg County was no place for easy foraging. North of Charlotte, near the present-day communities of Huntersville and Cornelius, lay the farm of John McIntyre. What unfolded there on October 3, 1780, became one of the most famous small actions of the Southern Campaign — a story retold for generations as proof that even farmers could sting an empire.

The Foraging Party

With Cornwallis’s army encamped in Charlotte, the British faced the constant problem of supplies. Foraging parties were sent out daily to gather food, livestock, and wagons from nearby farms. On this day, a large British detachment marched toward McIntyre’s farmstead, expecting to seize cattle and provisions with little opposition.

The Militia Ambush

But the British were not alone. A small band of Patriot militia — perhaps no more than a dozen men — had shadowed the foragers. From cover behind fences and trees, they opened fire. Startled and confused, the British fell into disarray. Accounts describe them abandoning wagons, dropping supplies, and fleeing in panic. Some ran so quickly they left their coats, muskets, and even cattle behind.

A Sting Beyond Its Size

Militarily, the clash at McIntyre’s Farm was minor. Few were killed on either side. But symbolically, it was a thunderclap. A handful of Carolina farmers had routed a professional British foraging column. For locals, the message was clear: the “Hornet’s Nest of Rebellion” was alive and buzzing, even beyond Charlotte’s crossroads.

Joseph Graham’s Memory

The reason this skirmish is remembered today owes much to Joseph Graham, a young militia officer who fought in many of Mecklenburg’s Revolutionary battles. Severely wounded at the Battle of Charlotte, Graham later recorded his experiences in detailed accounts. His writings preserved stories like McIntyre’s Farm for posterity, ensuring that future generations understood the courage of local men who defended their homes.

Huntersville & Cornelius Heritage

Today, the site of McIntyre’s Farm lies within the fast-growing corridor of Huntersville and Cornelius, communities that still take pride in their Revolutionary roots. While highways and neighborhoods cover the farmland now, the story of October 3 lives on as a reminder that even small skirmishes shaped the destiny of the Revolution.

V. The Battle of Cowan’s Ford (February 1, 1781)

The most dramatic Revolutionary War moment in the Lake Norman region came on the icy waters of the Catawba River, where Cowan’s Ford once offered a shallow crossing. Today, the site lies beneath the waters of Lake Norman, near Huntersville, Davidson, Cornelius, and Sherrills Ford. In 1781, it was the scene of a bloody stand that cost the life of one of North Carolina’s most respected Patriot generals.

Cornwallis on the Move

After the defeats at Kings Mountain and Blackstock’s, Cornwallis regrouped and began his push north into North Carolina. But January rains had swollen the Catawba River, creating a natural barrier between his army and Nathanael Greene’s retreating Continentals. Cornwallis needed to cross, and the most direct option was Cowan’s Ford.

Davidson’s Last Stand

General William Lee Davidson, a local leader from Mecklenburg County, rallied militia to defend the ford. On the cold morning of February 1, 1781, Davidson’s men lined the riverbank, firing into the British as they attempted to wade across in chest-deep water. The fight was desperate and close-range. Amid the smoke and confusion, Davidson himself was struck and killed. His death was a heavy blow to local morale, but his courage inspired resistance across the region.

A Delay with Big Consequences

Though the British eventually forced their way across, the skirmish at Cowan’s Ford bought General Nathanael Greene precious time to pull his army northward and prepare for the coming campaign. Greene’s strategy of delay — wearing down Cornwallis at every turn — relied on moments like Cowan’s Ford, where militia fought knowing they could not win but determined to slow the enemy.

Memory and Monuments

Today, the exact ford lies submerged under Lake Norman, but the memory of Davidson’s sacrifice endures. In 1905, the Daughters of the American Revolution erected a monument near the site in Huntersville. It honors Davidson as a martyr to North Carolina’s cause and remains a landmark of Revolutionary heritage in the Lake Norman area.

A Defining Lake Norman Battle

The Battle of Cowan’s Ford was not a victory, but it was defining. It symbolized the resilience of local communities — Huntersville, Davidson, Cornelius, Sherrills Ford, and the Catawba Valley — who refused to surrender even in the face of overwhelming odds. In many ways, Cowan’s Ford was the quintessential “Hornet’s Nest” battle: small in scale, costly in lives, but powerful in its sting.

VI. Torrence’s Tavern (February 2, 1781)

The day after the bloody stand at Cowan’s Ford, the British clashed once again with Patriot militia — this time at a tavern crossroads that would later sit near present-day Mooresville in Iredell County. Known as Torrence’s Tavern, the skirmish underscored how the war in the Charlotte backcountry seeped into every crossroads, farm, and community gathering place.

Retreating Militia

After General William Lee Davidson’s death at Cowan’s Ford, Patriot militia scattered into small groups. Many retreated northward toward Salisbury, but a contingent paused at Torrence’s Tavern, a well-known rest stop along the road. Some accounts suggest the men were weary, cold, and even drinking when they were caught off guard by the British.

Tarleton’s Ruthless Dragoons

British cavalry under Banastre Tarleton, infamous for his aggressive raids, struck quickly. His dragoons charged into the tavern yard and surrounding fields, cutting down the militia before they could form a proper defense. The clash was short but bloody, leaving Patriot bodies strewn around what had been a peaceful community gathering place.

Symbol of Backcountry Resistance

Though another tactical defeat, the fight at Torrence’s Tavern reinforced the pattern Cornwallis could not escape: every village, every crossroads, every tavern became a battlefield in Mecklenburg and Iredell Counties. Even after victories, the British paid a constant price in blood and exhaustion.

Legacy Near Davidson College

Torrence’s Tavern stood not far from where Davidson College would later be founded in 1837. Today, students walk the same ground where militia once fled Tarleton’s dragoons. The connection ties higher education in the Lake Norman region to its Revolutionary heritage, showing how institutions of learning grew from a landscape first marked by sacrifice.

A Lake Norman Story

For the communities around Mooresville, Davidson, Cornelius, and Huntersville, Torrence’s Tavern is a reminder that the Revolution was not fought only in distant capitals or on famous battlefields. It was fought in local taverns, at river fords, and on the farms of ordinary families — a fight that touched every corner of the Lake Norman backcountry.

VII. Other Skirmishes & Colorful Local Actions

Not every clash in the Charlotte backcountry earned the title of “battle,” but together, these dozens of smaller skirmishes and ambushes kept Cornwallis’s army in constant turmoil. The geography of Mecklenburg and the Lake Norman region — winding creeks, tavern crossroads, and family farms — became a natural battlefield where partisans struck again and again.

Sugaw Creek Ambushes

As Cornwallis withdrew from Charlotte in October 1780, his columns faced repeated attacks along Sugaw Creek (today spelled Sugar Creek). Local militia used the dense woods and swampy banks to stage hit-and-run ambushes. British soldiers, already wary after Charlotte and McIntyre’s Farm, found themselves stung at nearly every bend in the road. For residents of Huntersville and Cornelius, this proved the Revolution was not just about big battles but about defending every homestead and crossroad.

The Battle of the Bees

Among the most colorful local legends is the so-called “Battle of the Bees.” During one skirmish near Sugar Creek, Patriot fire startled a British column. In the chaos, someone overturned a beehive. The furious swarm descended on the redcoats, stinging soldiers and scattering them into the woods. While hardly a conventional military tactic, the incident became symbolic: even nature itself seemed to join the cause of the “Hornet’s Nest of Rebellion.”

A Backcountry That Fought Everywhere

Skirmishes were not confined to Charlotte’s crossroads. Communities stretching north into Sherrills Ford and Denver also played their part. Every ford of the Catawba, every farmstead, and every tavern became a potential ambush point. For Cornwallis, there was no safe ground. For local families, the Revolution was not an abstract political struggle — it was a war waged on their doorsteps, barns, and fields.

Legacy of the “Stings”

These minor clashes rarely appear in national histories, but they mattered. Each one drained Cornwallis’s army of supplies, morale, and momentum. They also reinforced the mythos of Mecklenburg as unyielding — a region where even bees became soldiers. That persistence, from Huntersville to Cornelius to Sherrills Ford, was what gave lasting weight to Cornwallis’s frustrated nickname: the Hornet’s Nest of Rebellion.

VIII. The Wider Southern Campaign

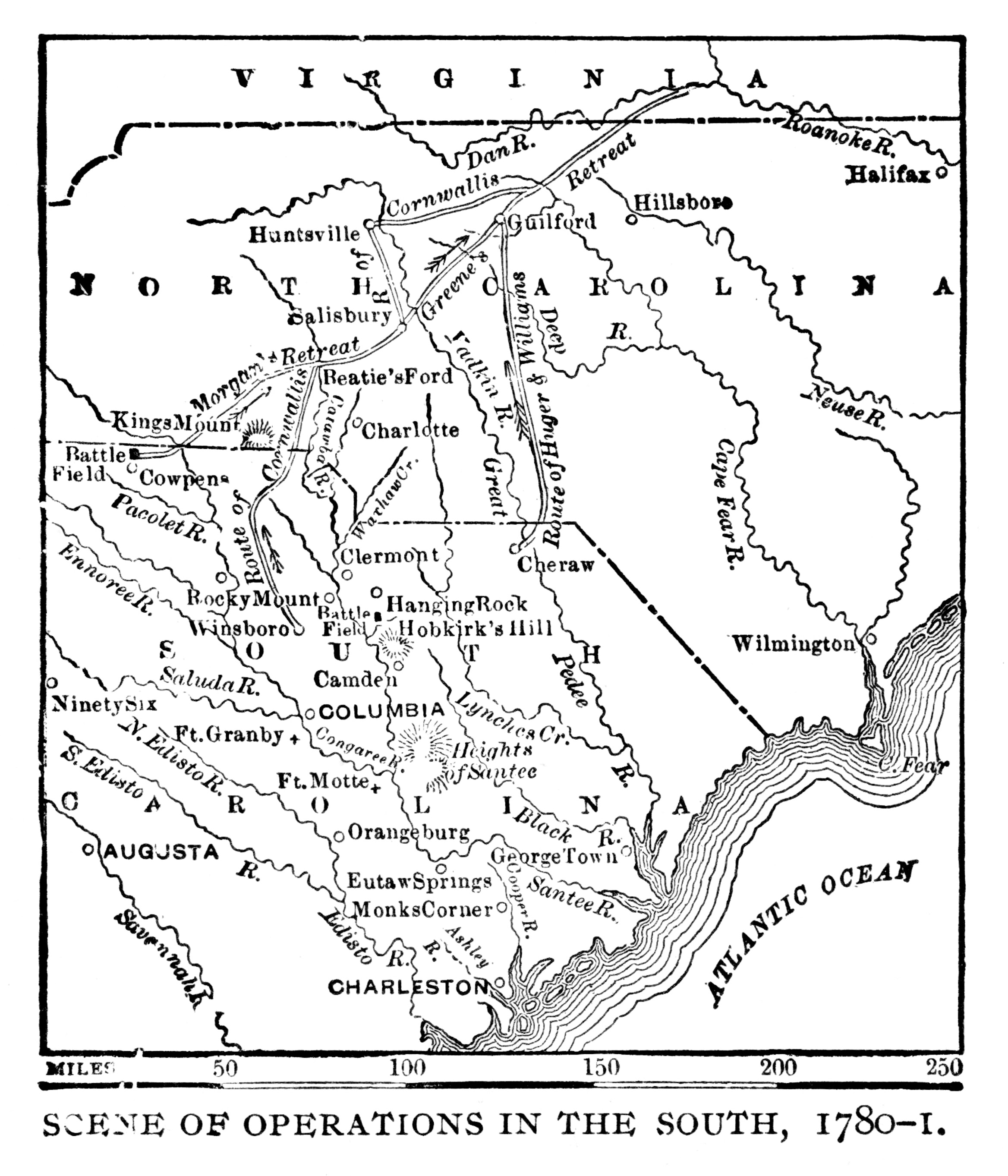

The clashes around Charlotte — from the courthouse square to McIntyre’s Farm, Cowan’s Ford, and Torrence’s Tavern — were part of a much larger story. The Southern Campaign of 1780–1781 would ultimately decide the outcome of the war. Though many of Charlotte’s fights were small, they connected directly to major battles that shifted the momentum of the Revolution.

Kings Mountain (October 7, 1780)

Just eleven days after the Battle of Charlotte, Patriot militia dealt Cornwallis a stunning blow at Kings Mountain, only 35 miles west of the Queen City. A force of backcountry riflemen — the famed Overmountain Men from Tennessee, Virginia, Wilkes County, and even the NC High Country towns near Boone and West Jefferson — surrounded and annihilated Major Patrick Ferguson’s Loyalist army. Ferguson was killed, and nearly all his troops were captured. For Cornwallis, the loss at Kings Mountain was devastating: his hope of rallying Loyalist support in the Carolinas collapsed overnight.

Guilford Courthouse (March 1781)

Months later, the war surged north to present-day Greensboro. On March 15, 1781, General Nathanael Greene faced Cornwallis at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse. Greene had drawn on reinforcements from across North Carolina, including men from Wilkes, Mecklenburg, and Rowan Counties. The battle was technically a British victory — Cornwallis held the field — but it came at staggering cost. Nearly a quarter of his army was killed or wounded. Cornwallis was forced to retreat to Wilmington, leaving the North Carolina backcountry effectively in Patriot hands.

Hobkirk’s Hill (April 1781) and Eutaw Springs (September 1781)

Greene’s strategy of attrition continued into South Carolina. At Hobkirk’s Hill (April 1781), he was defeated, but the British found themselves unable to hold the ground. Later, at Eutaw Springs (September 1781), Greene again withdrew, but the British were so battered they retreated to Charleston. The inland backcountry — stretching from Charlotte to Wilkesboro and beyond — was firmly back in Patriot control.

Yorktown (October 1781)

The sting of Charlotte, the mountain victory at Kings Mountain, and the attrition strategy of Greene culminated in Cornwallis’s retreat to Virginia. There, at Yorktown (October 19, 1781), Cornwallis surrendered to George Washington, effectively ending the war. The road to Yorktown ran straight through Mecklenburg County — paved with the skirmishes, sacrifices, and relentless resistance of the “Hornet’s Nest of Rebellion.”

Charlotte’s Place in the Arc of Victory

From the courthouse square in Uptown Charlotte to the ridges of Kings Mountain, from the fords of the Catawba near Lake Norman to the battlefields of Guilford Courthouse, Hobkirk’s Hill, and Eutaw Springs, the Southern Campaign was a chain of events linked together. Without the constant harassment in Charlotte and its surrounding towns — Huntersville, Cornelius, Mooresville, Davidson, Sherrills Ford, and Denver — Cornwallis might have secured the Carolinas. Instead, the backcountry stung him into exhaustion and defeat.

IX. Legacy of Charlotte’s Revolutionary Spirit

The Revolutionary War in Mecklenburg County left more than battlefield scars. It forged an identity that continues to shape Charlotte and the Lake Norman region today. The “Hornet’s Nest of Rebellion,” once a frustrated insult from Lord Cornwallis, became a badge of honor proudly worn by generations of Carolinians.

Monuments and Memorials

The memory of the Revolution lives on in monuments and cemeteries scattered across Huntersville, Cornelius, Davidson, Sherrills Ford, and Denver. Near Lake Norman, a DAR monument at Cowan’s Ford marks the spot where General William Lee Davidson fell defending the Catawba River. Historic cemeteries in Davidson and Huntersville contain the graves of Patriot soldiers and families who sheltered them. Roadside markers and memorial plaques throughout Mecklenburg and Iredell counties remind travelers that these suburban landscapes were once contested ground.

Civic Symbols in Charlotte

In Charlotte itself, the legacy of the “Hornet’s Nest” is visible everywhere:

- The Charlotte Hornets NBA franchise deliberately chose the name to honor Cornwallis’s famous remark.

- The Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police Department seal features a hornet’s nest.

- Parks, schools, and neighborhoods carry the name, from Hornets Nest Park to Hornets Nest Elementary.

What began as a scornful insult has become one of Charlotte’s most unifying civic symbols.

Davidson College and Revolutionary Roots

When Davidson College was founded in 1837, it was planted in the same ground once scarred by battles like Torrence’s Tavern and Cowan’s Ford. Though established decades after independence, the college carried forward the region’s heritage of resilience, faith, and learning — values rooted in the same backcountry spirit that defied Cornwallis.

A Regional Heritage

Charlotte’s Revolutionary story also resonates beyond Mecklenburg. To the west, towns like Newton and Wilkesboro in Wilkes County preserve their own backcountry legends, from the Overmountain Men of Kings Mountain to local militia who shadowed Cornwallis’s march. In the NC High Country, places like Boone and West Jefferson recall the mountain riflemen who streamed down into the Piedmont to fight at Kings Mountain. Together, these communities form a broader web of Revolutionary heritage, tying the Queen City to the mountains and foothills.

Enduring Identity

The Revolutionary War ended in 1781, but Charlotte never shed its identity as a hornet’s nest. Instead, the spirit of resistance, sacrifice, and community carried forward — shaping civic life, inspiring institutions, and becoming part of the cultural DNA of the entire Lake Norman and North Carolina Piedmont region.

X. From Backcountry Battles to Modern Charlotte

The story of the Revolution in Mecklenburg County was not written in sweeping armies or grand fortresses, but in crossroads, fords, farms, and taverns. From the courthouse square at Trade and Tryon to McIntyre’s Farm north of Huntersville, from the bloodied banks of Cowan’s Ford on today’s Lake Norman to Torrence’s Tavern near Mooresville, the Charlotte region earned its place in Revolutionary history through constant, stinging resistance.

Each of these encounters — whether a dramatic stand in Uptown Charlotte or a sudden ambush along Sugaw Creek — reinforced a simple truth: the British could march through, but they could never hold this land. Cornwallis’s army discovered that the backcountry would not yield quietly. What he dismissed as a “hornet’s nest of rebellion” became the proud identity of Charlotte and its neighbors.

That identity endures. Monuments near Huntersville and Sherrills Ford honor General William Lee Davidson, who gave his life at Cowan’s Ford. Davidson College, founded in 1837, rose near the ground where Patriot militia once clashed with Tarleton’s dragoons. Across Mecklenburg, Iredell, and Lincoln counties, cemeteries, markers, and memorials keep alive the memory of men and women who fought for independence.

The legacy reaches further still. In Newton, Wilkesboro, and the NC High Country towns of Boone and West Jefferson, Revolutionary spirit is remembered in the tales of Overmountain Men and backcountry militia who joined in the fight. These threads weave Charlotte into the larger fabric of the Southern Campaign — a struggle that began in disaster at Charleston, shifted at Kings Mountain, turned at Guilford Courthouse, and ended in triumph at Yorktown.

Today, Charlotte’s hornet’s nest identity is more than history. It is culture. The NBA’s Charlotte Hornets, the CMPD seal, neighborhood names, and even community parks reflect the sting Cornwallis once cursed. Around Lake Norman, in Huntersville, Cornelius, Davidson, Denver, and Sherrills Ford, Revolutionary landmarks stand alongside modern neighborhoods, tying past sacrifice to present community.

In the end, the battles of Charlotte remind us that victory is not always measured in size, but in spirit. The region’s small fights delayed armies, inspired resistance, and shaped the course of a nation. Cornwallis’s frustration became Charlotte’s pride, and the “hornet’s nest” still buzzes — a lasting symbol of courage, defiance, and civic identity in the Queen City and the Lake Norman backcountry.

Adkins Law, PLLC – A Law Firm Located in Huntersville

📞 Adkins Law, PLLC — Serving Huntersville & Lake Norman

At Adkins Law in Huntersville, we understand the importance of family, community, and legacy. Just as the Charlotte and Lake Norman region built its identity through resilience in the Revolutionary War, we stand ready to help you protect what matters most today.

Whether you need guidance in family law, child custody, divorce, estate planning, or mediation, our experienced team is here to walk with you through life’s most important challenges. We proudly serve neighbors across Huntersville, Cornelius, Davidson, Sherrills Ford, Denver, Charlotte, Mountain Island Lake, and the broader Lake Norman and NC High Country communities.

Leave a Reply