Overview

The Battle of New Garden Meeting House, fought on the morning of March 15, 1781, was one of the most intense and consequential pre-battle engagements of the Southern Campaign of the American Revolutionary War. Occurring just hours before the Battle of Guilford Courthouse, this skirmish unfolded across the Great Salisbury Road (modern New Garden Road) near the New Garden Friends Meeting House, a Quaker community west of Greensboro, North Carolina.

At first light, Lt. Col. Henry “Light-Horse Harry” Lee’s Continental cavalry and riflemen collided with Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton’s British Legion dragoons, supported by German Jägers and infantry from the Guards and Welsh Fusiliers. The combat was fierce—sabers clashing, muskets firing, and horses thundering through the fog-laced fields of Guilford County.

For nearly three hours, the battle surged across several miles of countryside. The Patriots advanced, fell back, and counterattacked through three separate positions—around the Quaker meetinghouse, the surrounding farms, and the road north toward Guilford Courthouse. Both sides fought with desperation and skill; Tarleton was wounded in the hand, while Lee narrowly escaped injury when his startled horse threw him amid heavy fire.

Though fought at brigade level, the engagement carried strategic weight far beyond its scale. Lee’s men, along with attached Virginia riflemen and North Carolina militia—including volunteers from Mecklenburg County and the Huntersville–Lake Norman region—successfully delayed Lord Cornwallis’s column. Their stand gave Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene the vital hours he needed to establish his defensive lines north of the county seat, setting the stage for the larger and bloodier confrontation later that morning.

The Battle of New Garden Meeting House was not merely a skirmish; it was a crucial opening act in the drama of Guilford Courthouse—a clash that combined cavalry prowess, local resistance, and Quaker compassion in the heart of North Carolina’s Piedmont.

Forces and Commanders

American Command

Lt. Col. Henry “Light-Horse Harry” Lee – Commander, Lee’s Legion (Virginia)

Approx. 1,077 men, comprising one of the most balanced Patriot light corps of the Southern Campaign.

Order of Battle:

- Lee’s Legion Cavalry and Infantry (VA): Elite Continental light troops trained for reconnaissance, raiding, and screening operations. Commanded directly by Lee, with Captains James Armstrong, Joseph Eggleston, Michael Rudolph, Allen McClane, and Henry Archer leading subordinate troops.

- Col. William Campbell’s Riflemen (VA): Veterans of King’s Mountain, drawn from Augusta and Rockbridge Counties in western Virginia. Renowned for marksmanship, they fought as mobile light infantry armed with long rifles.

- Virginia Militia Detachments: Reinforced by men under Col. Charles Lynch and Maj. John Taylor, these units provided flexible skirmish lines behind Lee’s core legion.

- North Carolina Light Troops and Scouts: Local militia from Guilford, Caswell, and Mecklenburg Counties, including small detachments from the Catawba River valley and Huntersville region who had fought earlier at Cowan’s Ford and Clapp’s Mill.

- Attached Artillery Support: Minimal—two light field pieces accompanying Greene’s advance guard but not engaged directly at New Garden.

Strength & Capability:

Lee’s force excelled in mobility and coordination, combining cavalry shock power with precision rifle fire. They served as the eyes and shield of Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene’s army, delaying and observing Cornwallis’s advance while gathering real-time intelligence for the main battle at Guilford Courthouse.

British Command

Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton – Commander, British Legion Cavalry

Approx. 1,232 men, forming the striking vanguard of Lord Cornwallis’s army.

Order of Battle:

- British Legion Dragoons: Tarleton’s feared green-jacketed cavalry, veterans of Monck’s Corner, Cowpens, and Pyle’s Defeat. Known for their discipline, speed, and ferocity in pursuit.

- Hessian Jägers: German riflemen skilled in woodland fighting, often used as skirmishers and forward marksmen.

- Regiment von Bose (Hessian Line Infantry): Regular German infantry under seasoned European officers, providing steady line support behind Tarleton’s horse.

- Guards Light Infantry (British Army): Elite troops under Capt. Francis Dundas, famed for their precision and aggressive maneuvering.

- 23rd Regiment of Foot – Royal Welch Fusiliers: A professional line unit drawn from Cornwallis’s main army, committed to reinforce Tarleton’s right flank during the action.

- Loyalist & Provincial Cavalry Auxiliaries: Small detachment of mounted Loyalists and Tory scouts familiar with the local terrain.

Strength & Capability:

Tarleton’s mixed force was fast, disciplined, and lethal, designed for pursuit and shock action. However, his units were fatigued and hungry, having marched before dawn from Deep River. Their engagement at New Garden, followed immediately by the main battle at Guilford Courthouse, left many men and horses exhausted and under-supplied by day’s end.

Command Dynamics

The clash at New Garden Meeting House was as much a test of commanders as it was of armies—a contest between two of the most daring cavalry leaders of the American Revolution.

Henry “Light-Horse Harry” Lee, commanding under Col. Otho Williams within Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene’s Light Corps, served as the eyes and shield of the Continental Army. Williams’s Light Corps was a handpicked detachment of fast-moving infantry, cavalry, and riflemen whose mission was to probe the enemy, screen the army’s movements, and buy time for Greene to choose his ground. Lee, just twenty-five years old, had already earned national fame for his bold raids in New Jersey and Virginia and for his vital role in the Battle of Cowpens earlier that year. Greene trusted Lee’s instinctive understanding of terrain, mobility, and timing—qualities that made him one of the Revolution’s most effective light horse officers.

Facing him once again was Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton, commander of the British Legion and advance guard of Lord Charles Cornwallis’s army. Tarleton was the very embodiment of aggressive warfare. Young, charismatic, and ruthless, he had led British dragoons to devastating victories in South Carolina at Monck’s Corner and Waxhaws, earning the grim sobriquet “Bloody Tarleton” among Patriot survivors. He answered directly to Cornwallis, who viewed his Legion as the spearpoint of the British army in North Carolina—a force meant to scout, strike, and scatter opposition before the main body advanced.

By March 1781, the two men were well acquainted adversaries. They had first confronted each other indirectly at Cowpens (January 1781), where Daniel Morgan’s Patriot army—supported by Lee’s detachments—had annihilated Tarleton’s force, killing or capturing nearly 90% of his command. Weeks later, their paths crossed again in the aftermath of Pyle’s Massacre (February 1781), where Lee’s Legion disguised itself as Tarleton’s men and destroyed a Loyalist militia column marching to join Cornwallis. Then, at Clapp’s Mill (March 2–4, 1781), Lee and Tarleton sparred once more in a swift, indecisive engagement along Beaver Creek in Alamance County. By the time they met at New Garden, the rivalry had become personal—a duel of wits and reputation between two cavalrymen whose methods could not have been more different.

Lee fought with intellect and restraint. He used deception, precision, and small-unit coordination to wear down his enemy and serve Greene’s greater purpose—delay, observe, and survive. Tarleton, by contrast, believed in momentum and terror: charging headlong to destroy an opponent’s morale before they could organize resistance. To Tarleton, speed and ferocity were the tools of victory; to Lee, patience and control were the keys to survival.

At New Garden, those philosophies collided for the final time. Tarleton sought to break through the American screen and clear the road to Guilford Courthouse; Lee intended to hold the field long enough to cripple the British advance. The forces they commanded were remarkably similar in strength—each with about 1,000 to 1,200 men—and both composed of elite, battle-hardened troops accustomed to rapid movement and flexible command. Yet their missions were mirror images: Tarleton to strike, Lee to stall.

Their duel symbolized the larger contest between their superiors: Cornwallis and Greene. One sought to crush rebellion through decisive battle; the other aimed to outlast and exhaust the British through maneuver. In that sense, the fight at New Garden became a microcosm of the entire Southern Campaign—a struggle between aggression and endurance, conquest and survival, dominance and defiance.

By the time the two cavalrymen disengaged that morning, each had fulfilled his role: Tarleton cleared the road, but at a cost in blood and time that would haunt Cornwallis at Guilford Courthouse. Lee withdrew, battered but intact, having accomplished the one task Greene had given him: delay the enemy long enough for freedom to find its footing.

Prelude to Battle

In the early morning darkness of March 15, 1781, Lord Charles Cornwallis broke camp near the Deep River Meeting House, determined to destroy Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene’s Continental army. At 2:00 a.m., he ordered his baggage train under escort to Bell’s Mill for safekeeping, then marched north with his main column—nearly 2,000 men—along the Great Salisbury Road toward Guilford Courthouse. His troops were cold, hungry, and weary from months of chasing Greene across the Carolinas, but Cornwallis was convinced that one more decisive victory could crush Patriot resistance in the South.

By 9:00 a.m., the advance guard—Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton’s British Legion—rode several miles ahead of the main force. Tarleton’s cavalry, famously aggressive and disciplined, had served as the spearpoint of Cornwallis’s army since the Charleston campaign. But waiting for them on the wooded ridges north of the New Garden Friends Meeting House was a commander who knew Tarleton’s every tactic: Lt. Col. Henry “Light-Horse Harry” Lee of Virginia.

Lee had fought Tarleton’s dragoons before—at Monck’s Corner, Cowpens, and Pyle’s Defeat—and understood his rival’s methods. Both men were young, ambitious, and fiercely confident, their reputations built on lightning cavalry maneuvers and personal daring. But while Tarleton led his Legion with blunt, almost reckless aggression, Lee combined precision with cunning—a strategist who prized deception and timing over brute force.

That morning, Lee’s scouts—many of them North Carolina militia horsemen drawn from the Huntersville and Lake Norman region—spotted Tarleton’s column winding up the Great Salisbury Road. In a carefully planned ambush, Lee unleashed his forward cavalry detachment. The Americans struck with devastating effect, catching the British by surprise.

“The whole of the enemy’s section was dismounted,” Lee later wrote, “many of the dragoons killed, the rest made prisoners: not a single American soldier or horse injured.”

This sudden reverse shocked Tarleton, who quickly rallied his surviving dragoons and redirected his line of advance to avoid a repeat. Lee, realizing that Cornwallis’s main army could not be far behind, disengaged and withdrew toward the New Garden Friends Meeting House—a landmark known to both sides.

There, Lee arranged his riflemen, militia, and Legion infantry along the narrow lane and positioned his cavalry to guard the flanks and rear. Behind him, Col. William Campbell’s Virginia mountaineers took cover among the trees, ready to deliver accurate rifle fire against the next British advance.

As Lee reformed his lines, the two opposing cavalry commanders—veterans of multiple duels across the Carolinas—prepared to meet yet again. The upcoming engagement at New Garden would be their fourth direct confrontation in as many months, each encounter escalating in scale and ferocity. And though neither knew it, this would be the last time Lee and Tarleton faced each other in battle.

Across the fields of Guilford County, the still morning air was about to erupt into chaos—the crack of muskets, the clash of sabers, and the roar of hooves that would announce the start of one of North Carolina’s most dramatic mornings of the Revolution.

The Battle: March 15, 1781

At about 10:00 a.m., Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton’s detachment of dragoons—supported by Hessian Jägers, German infantry of the Regiment von Bose, and the Guards Light Infantry under Capt. Francis Dundas—advanced swiftly up the Great Salisbury Road toward the New Garden Friends Meeting House. The narrow lane cut through open farmland and scattered timber, forcing both armies into tight columns where cavalry and infantry could clash at close range.

Lee’s Legion, reinforced by Col. William Campbell’s Virginia riflemen, held the high ground north of the meetinghouse. When Tarleton’s cavalry appeared through the trees, Lee’s men countercharged, sparking one of the most furious small-unit fights of the Southern Campaign.

For nearly half an hour, the road and surrounding fences echoed with musketry and saber blows. Smoke and dust obscured the fields, while horses screamed and collided amid the thunder of hooves. Tarleton himself was struck in the right hand, losing two fingers, but he refused to quit the fight.

Lee later recalled the moment with vivid detail:

“As I reached the meetinghouse, the British Guards had just displayed in line and gave the American cavalry a close and general fire. The sun had just risen above the trees, and shining bright, the refulgence from the British muskets frightened my horse so as to compel me to throw myself off.”

Remounting instantly, Lee ordered a tactical withdrawal. His Legion infantry formed into disciplined ranks and unleashed a volley of musket fire against the advancing Guards, while Campbell’s riflemen on the left delivered accurate, deadly shots from the cover of trees and rail fences.

The fighting shifted back and forth across the meetinghouse grounds and down the road toward the crossroads. At one point, British light infantry and Loyalist auxiliaries attempted to flank Lee’s left, only to be driven off by combined rifle and carbine fire. Meanwhile, Lee’s cavalry regrouped behind the line, ready to cover the retreat if Cornwallis’s main body appeared.

Tarleton, regrouping after his wound, later conceded in his memoirs:

“The fire of the Americans was heavy, and the charge of their cavalry spirited; notwithstanding their numbers and opposition, the gallantry of the light infantry of the Guards… made impression upon their center before the 23rd Regiment arrived to give support.”

The 23rd Regiment—the Royal Welch Fusiliers—arrived just in time to stabilize Tarleton’s advance, but the delay had already achieved Greene’s purpose. Lee, observing the dust clouds of Cornwallis’s main army approaching from the south, knew that further resistance would invite destruction. He ordered a controlled withdrawal, falling back methodically toward Greene’s prepared position at Guilford Courthouse.

It was, tactically, a textbook example of Greene’s war of movement—to fight, delay, and survive rather than risk annihilation. Lee’s troops had bloodied Tarleton yet again and bought Greene the crucial hours he needed.

Casualties and Command Observations

| Side | Killed/Wounded | Captured | Total Casualties |

| American | ≈17 | – | 17 |

| British | ≈31 | – | 31 |

Contemporary reports confirm heavier British losses, including Captain Goodrick of the Guards and several officers from Tarleton’s Legion. The British Light Infantry, already fatigued from their night march, suffered disproportionately in the close-range volleys around the meetinghouse.

While the numbers seem modest, their strategic effect was outsized. Cornwallis lost time, initiative, and momentum. Tarleton’s horsemen—so critical in the coming main battle—entered the field at Guilford Courthouse bloodied, leader-wounded, and partially disorganized.

Command Rivalry: Lee and Tarleton

This encounter marked the fourth direct confrontation between Henry Lee and Banastre Tarleton in less than four months—a rivalry unmatched among Revolutionary cavalrymen.

- At Monck’s Corner (1780), Tarleton routed Patriot dragoons early in the campaign.

- At Cowpens (January 1781), Lee helped secure the American victory that shattered Tarleton’s Legion.

- At Pyle’s Defeat (February 1781), Lee’s men annihilated a Loyalist militia column Tarleton had promised to reinforce.

- And here, at New Garden, the two adversaries met for the last time—both wounded, both defiant, and both shaping the day’s outcome in different ways.

Their duel embodied the collision of two philosophies of war: Tarleton’s relentless aggression versus Lee’s cunning economy of force. In this final meeting, Lee prevailed by patience, executing the perfect delaying action that fulfilled Greene’s broader strategy.

Outcome and Significance

The Battle of New Garden Meeting House was both a tactical American victory and a strategic masterstroke in Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene’s Southern Campaign. Though small in numbers, the action achieved everything Greene intended—to delay, disrupt, and disorient Lord Cornwallis’s advance on Guilford Courthouse.

Lt. Col. Henry “Light-Horse Harry” Lee’s compact, disciplined corps had engaged and bloodied Cornwallis’s vanguard, forcing the British to halt, regroup, and spend nearly three critical hours re-forming their lines before reaching Greene’s main position. That delay gave Greene the time he needed to place his artillery, organize the militia lines, and rest his men—preparing for one of the most important confrontations of the war.

The battle also sapped British energy and morale. Cornwallis’s troops had marched before dawn without food or rest, and by the time they arrived at Guilford Courthouse, many were already exhausted and shaken. Tarleton’s Legion—his once-feared cavalry—entered the main battle with reduced numbers, wounded officers, and horses spent from hours of fighting.

For the Americans, the engagement at New Garden demonstrated the growing maturity of Greene’s army. The coordination between Lee’s Legion, Campbell’s riflemen, and the North Carolina militia (including detachments from Mecklenburg and Huntersville) reflected a new level of professionalism in Patriot command. What had begun months earlier as a patchwork of state militias and Continental remnants was now a force capable of executing precise delaying actions under pressure.

Historians also view the encounter as a symbolic closing chapter in the duel between Henry Lee and Banastre Tarleton, two of the Revolution’s most skilled and bitterly opposed cavalry leaders. The two had shadowed each other across the Carolinas—from Cowpens to Pyle’s Defeat, Clapp’s Mill, and now New Garden. Each battle had defined a phase of Greene’s war of attrition, and at New Garden, their rivalry reached its climax. Both men were wounded—Tarleton’s hand shattered, Lee thrown and nearly trampled—yet neither yielded until duty compelled withdrawal.

While New Garden lacked the scale of Guilford Courthouse or King’s Mountain, its strategic ripple effect was undeniable. The skirmish directly set the tempo of the Guilford battle, contributing to Cornwallis’s costly “victory” that crippled his army and pushed him toward Wilmington—and eventually, surrender at Yorktown seven months later.

In this sense, New Garden embodies the essence of Greene’s campaign: winning by not losing, bleeding the British by inches, and forcing the enemy’s strength to become its weakness. What began as a rural clash near a Quaker meetinghouse became a key turning point in the Carolina backcountry’s march toward independence.

Quaker Neutrality and Compassion

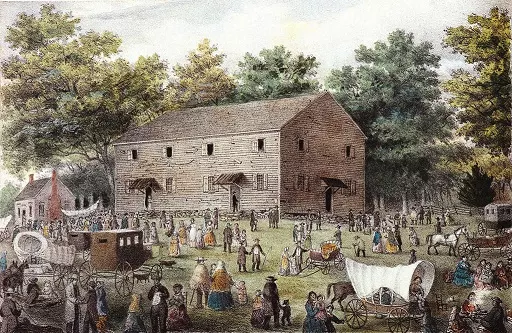

The battle unfolded around the New Garden Friends Meeting House, established by Quakers in 1748. For decades, this small community had lived in peace, guided by their founder George Fox’s belief in the Inner Light — the divine spirit residing within every human being. The Friends rejected warfare, oath-taking, and political allegiance, pledging loyalty only to God and conscience.

When the Revolution erupted, Quakers across North Carolina faced painful dilemmas. Many refused to take oaths of allegiance or to bear arms, which led to fines, confiscations, and even disownment by some meetings. Yet, as battles spread into the Piedmont, neutrality became impossible. The New Garden community, located on the main road between Salisbury and Guilford Courthouse, found itself directly in the path of two armies.

On the morning of March 15, 1781, they awoke to the thunder of hooves and gunfire as Lee’s Legion and Tarleton’s dragoons fought across their farmland. Only hours later, the dead and wounded lay among the trees and fields surrounding the meetinghouse.

In the days following New Garden and Guilford Courthouse, both General Nathanael Greene and Lord Charles Cornwallis appealed to the Quakers for help caring for the wounded. True to their faith, the Friends opened their doors to all, tending to American and British soldiers alike. The meetinghouse, its barns, and nearby homes became makeshift hospitals for more than 250 wounded men, despite the dangers of smallpox and infection.

Their compassion came at a price. Several caregivers fell ill, including Richard Williams, who died from the disease, and Nathan Hunt, who survived and continued as a leading Quaker minister after the war. Letters and meeting minutes describe their selfless service: the Friends fed, nursed, and buried soldiers without regard to nationality or uniform.

“They observed no political or ideological differences in the deceased,” one Quaker record noted, “but interred them in a single grave behind the meetinghouse.”

That grave still exists today — a long, unmarked mound within the cemetery of the New Garden Friends Meeting on New Garden Road — the resting place of British redcoats, American Continentals, and local militia buried side by side.

Their quiet courage earned the gratitude of both commanders. Greene wrote to the Quakers, thanking them for their “relief of the suffering wounded at Guilford Court House,” while Cornwallis’s staff praised their impartial mercy. In a time of vengeance and division, the Friends’ actions embodied the purest form of Christian service.

Broader Quaker Legacy

The compassion shown at New Garden was not an isolated act. Across North Carolina, Quaker communities in Cane Creek, Deep River, and Hopewell (near present-day Huntersville) offered similar relief to refugees and soldiers during the war. Many of these families were part of the same migration network that had carried the Society of Friends from Pennsylvania and Virginia into the Carolina Piedmont.

The events of 1781 deepened Quaker commitment to peace and service. In later decades, New Garden Friends became leaders in abolition, education, and Native American outreach, founding institutions like the New Garden Boarding School (1837) — today’s Guilford College.

Through war and peace, the Friends of New Garden upheld the conviction that all people, regardless of creed or cause, share the same divine light. Their example transformed a battlefield into a sanctuary — and a moment of violence into a legacy of humanity that still endures in North Carolina’s Quaker heritage.

Aftermath

In the weeks following the battle, the New Garden friends meeting faced devastation. Their crops were trampled, their food stores depleted, and their livestock seized by both armies. Yet the Quakers’ humanitarian mission did not end with the gunfire. They continued to care for the wounded left behind, nurse the sick, and bury the dead—acts of mercy carried out in a community that had been stripped bare by war.

Letters from the period describe how friends sacrificed their remaining supplies to feed soldiers and refugees alike, embodying their testimony of peace even amid hunger and loss. When General Nathanael Greene wrote to thank them for their “relief of the suffering wounded,” the meeting replied humbly that they would “do all that lies in our power” to aid the afflicted.

The physical toll was immense. The original meetinghouse, built of rough-hewn timber in 1748, was damaged during the fighting and burned in 1784, possibly due to the lingering sparks of campfires or accidental ignition from nearby military activity. Rebuilt in 1791, the new structure served a growing community of Quakers who, even after war, remained steadfast in their pacifist principles.

Over the next century, the New Garden community transformed from a frontier meeting into a hub of Quaker education, reform, and social leadership. In 1837, the Friends established the New Garden Boarding School to educate young men and women according to Quaker values of equality and enlightenment. That school evolved into Guilford College in 1888, one of the oldest coeducational institutions in the South and the first college in North Carolina founded by religious pacifists.

The surrounding area—once the site of the Battle of New Garden Meeting House—became a place of learning, service, and progressive thought. The same soil that had soaked up the blood of soldiers now nurtured an institution that championed education, conscience, and reconciliation.

By the mid-1800s, many Quaker families from New Garden, Hopewell, and Cane Creek (including those near present-day Huntersville) were instrumental in founding schools, abolitionist efforts, and the Underground Railroad network that helped enslaved people escape north. Their moral courage extended the legacy of 1781 from the battlefield to the broader struggle for freedom and equality.

Today, the New Garden Friends Meeting still stands at 801 New Garden Road in Greensboro, just a few miles from Guilford Courthouse National Military Park. The congregation remains active, hosting worship and community events on the same ground where cavalry once clashed and wounded soldiers once found sanctuary. Its quiet cemetery—containing the shared grave of British and American soldiers—reminds visitors that faith, compassion, and forgiveness can endure even in the aftermath of war.

The Battlefield Today

📍 Location: Intersection of New Garden Road and West Friendly Avenue, Greensboro, North Carolina

📍 Coordinates: 36.0903° N, 79.8817° W

📍 Marker: North Carolina Historical Marker J-40, dedicated in 2010

The site of the Battle of New Garden Meeting House lies just west of downtown Greensboro in what is now a peaceful suburban community centered around Guilford College and the New Garden Friends Meeting. The modern road network follows much of the original Great Salisbury Road, the same route on which Lee’s Legion and Tarleton’s dragoons clashed on that March morning in 1781.

The battlefield extends across portions of the Guilford College campus, the New Garden Friends Meeting grounds at 801 New Garden Road, and surrounding neighborhoods that trace the line of the original encounters. Interpretive markers and walking paths along New Garden Road guide visitors through the key stages of the engagement—

- the initial cavalry ambush north of the meetinghouse,

- the intense firefight and saber combat around the meetinghouse itself, and

- the Patriot withdrawal northward toward Guilford Courthouse National Military Park.

At the corner of New Garden Road and Friendly Avenue, the bronze-cast Historical Marker J-40 summarizes the morning’s events and connects them to the larger Battle of Guilford Courthouse. The marker is maintained by the North Carolina Office of Archives and History, while interpretive exhibits at the Guilford Courthouse National Military Park (five minutes away) provide maps and artifacts illustrating how the two engagements flowed together into a single day of combat.

Visitors can still sense the contrast between the serenity of the Quaker landscape and the violence it once witnessed. Beneath the trees and quiet streets of modern Greensboro, the faint contours of the 1781 battleground remain visible—gentle slopes where cavalry once charged and fields where Quakers later buried British and American soldiers together.

The New Garden Friends Meeting cemetery, located just behind the meetinghouse, remains one of the most poignant Revolutionary War sites in the Piedmont. A long, brick-outlined grave marks the final resting place of men from both sides—an enduring symbol of reconciliation.

Today, Guilford College carries forward that spirit of reflection and learning. Founded by the same Quaker community that tended the wounded, it now welcomes students from across the world to study on the very ground where compassion triumphed over conflict.

For travelers from the Huntersville and Lake Norman region, the drive to the site takes roughly 90 minutes north via I-77 and I-40, making it a convenient and historically rich day trip that ties directly to other Revolutionary War landmarks across the Carolina backcountry—Cowan’s Ford, Clapp’s Mill, and Guilford Courthouse itself.

📍 Coordinates: 36.0903° N, 79.8817° W. The modern day location of the Battle of New Garden Meeting House

Legacy

For generations, the Battle of New Garden Meeting House has been overshadowed by the larger Battle of Guilford Courthouse fought just hours later. Yet modern historians increasingly recognize New Garden as a stand-alone engagement—one involving more than 2,000 soldiers, three distinct phases of combat, and a measurable impact on the course of the war in the Carolinas.

This was not merely a prelude; it was a critical action in its own right. The skirmishes that morning delayed Lord Cornwallis’s advance, bloodied his vanguard, and sapped the energy of his troops before the decisive clash at Guilford Courthouse. It was also the fourth and final confrontation between Lt. Col. Henry “Light-Horse Harry” Lee and Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton, whose rivalry—spanning Cowpens, Pyle’s Defeat, Clapp’s Mill, and now New Garden—symbolized the brutal chess match of the Southern Campaign.

Beyond tactics and rivalries, New Garden stands as a moral landmark in North Carolina’s Revolutionary history. The Quakers of the New Garden Friends Meeting, guided by their pacifist convictions, turned their war-torn community into a refuge for the suffering. In a conflict often remembered for its divisions—Patriot versus Loyalist, neighbor against neighbor—the Friends chose mercy and unity. Their meetinghouse became a hospital where British and American wounded lay side by side, tended by the same hands that would later build Guilford College, one of the state’s enduring centers of conscience and learning.

The story of New Garden also connects seamlessly to the broader web of Revolutionary War battles across North Carolina’s Piedmont—each part of a chain of endurance that shaped the Southern Campaign:

- Battle of Cowan’s Ford (February 1, 1781) – Mecklenburg County militia resisted Cornwallis’s crossing of the Catawba River, inflicting early casualties and delaying the British march.

- Battle of Pyle’s Massacre (February 25, 1781) – Henry Lee’s Legion annihilated a Loyalist column near present-day Graham, crippling Cornwallis’s hopes of raising Loyalist support.

- Battle of Clapp’s Mill (March 2–4, 1781) – A fierce skirmish at Beaver Creek in Alamance County where Lee and Otho Williams ambushed Tarleton’s dragoons.

- Battle of Shallow Ford (October 14, 1780) – A Patriot victory along the Yadkin River that broke Loyalist momentum in the western Piedmont.

- Battle of Lindley’s Mill (September 13, 1781) – A later Alamance County fight where Loyalists ambushed Patriots escorting Governor Thomas Burke, showing that civil strife continued even after Cornwallis’s retreat.

Together, these engagements trace a continuous corridor of struggle—from the Catawba River near Huntersville to the Quaker farmlands of New Garden—revealing how ordinary North Carolinians shaped the Revolution through persistence rather than grand battles.

The legacy of New Garden is, therefore, twofold: military precision and moral conviction. On the one hand, Lee’s soldiers executed a textbook delaying action that directly influenced the outcome at Guilford Courthouse. On the other, the Quakers of New Garden transformed the battlefield into sacred ground—a place of peace, equality, and forgiveness.

From the river crossings of Huntersville to the hallowed cemetery of the New Garden Friends Meeting, the events of 1781 remind us that independence was secured not only by musket and saber, but also by the quiet courage of those who chose compassion in a time of war.

Adkins Law, PLLC: A Law Firm Located in Huntersville NC

Adkins Law, PLLC in Huntersville, North Carolina, proudly serves the Lake Norman and Charlotte region. Led by Attorney Christopher Adkins, the firm focuses on family law, divorce, custody, mediation, and estate planning, offering trusted guidance with experience and integrity.

Leave a Reply